Understand what type of player you are and adjust your style accordingly

My Danish teammate Grandmaster Sune Berg Hansen mentions Foundation of Chess Strategy by another Danish Grandmaster, Lars Bo Hansen, as the chess book that has had the greatest influence on his own chess. It is not so much the explanations or the chess in the book, but the concept of dividing players into four categories that made an impression on Sune.

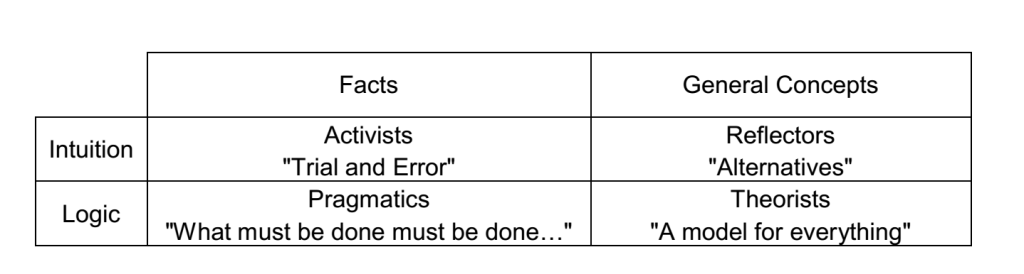

Lars Bo Hansen puts a name to four types of players and debates how they should play and how to play against them. They are: Activists, Reflectors, Pragmatics and Theorists.

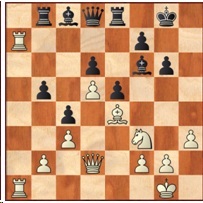

They are divided into a grid that looks like this:

Lars Bo Hansen describes the inherent characteristics of each player, their strengths and weaknesses and so forth. While I find the chess a bit uninspired in the book, I do find the concept extremely useful and would recommend anyone to read this book and identify themselves in the grid.

The point to this is that the idea of the all-round player is close to being an illusion. Of all the World Champions the only one continuously mentioned as an all-rounder is Boris Spassky and I have a feeling that this is as much tradition as it is fact. And anyway, the ‘narrow-minded’ players who beat him up in matches, Petrosian, Karpov and Fischer all stand above him in chess history as far as I am concerned.

So, what we should do is design our opening repertoire according to our style and slowly improve in the areas where we are weak (avoiding them at all costs usually means a lot of rating points). But there are parts of chess that are better suited to our way of thinking, to our character and so on.

A final note on Hansen’s book: The references to business are poor as far as I am concerned and could with benefit be ignored entirely. Luckily they quickly disappear from the book. The idea of this particular grid does not originate in the world of business anyway; as with so many other things, it was thought up in Russia. I first saw it in Mark Dvoretsky’s writings as a brief note so it is possible the idea was his to start with.

Recent Comments