The Lazy World Champion?

In the 60 minutes segment on Magnus Carlsen a few years ago Friedrich Friedel (the journalist behind www.chessbase.com) called Carlsen a bit lazy. Others have tried to put this label on the new World Champion, but I personally never bought it. And if you checked the recent Norwegian documentary on Carlsen, you will at one point see Henrik Carlsen rubbish the claim, stating that Carlsen has looked as much at chess as anyone else of the same age.

The new World Champion is an excellent example of a number of abilities.

First of all, more than anything, incredible determination. In Chennai Carlsen was wrapped in a bubble with no contact with anyone outside his team. Even when he was relaxing in the bowling hall, his thoughts were on the match. A journalist and photographer tried to get a photo of Carlsen somewhere else than the playing hall. Espen Agdestein, Carlsen’s manager (and brother of Simen) saw the journalists and gave them two and a half minute to take a discreet photo, but the Indian bodyguards got to them before they got even a single snap.

Secondly he has a fantastic psyche. He is not made of Teflon as some people believed before London. We should not forget that people react differently to success and to failure. Roger Federer was always the greatest gentleman in tennis – while he was winning. After he stopped winning his behaviour was more erratic and less pleasant. With Carlsen we saw him react differently to playing the Candidates than to playing in Wijk aan Zee. What is important is not that Carlsen has an emotional experience under pressure, but that he managed to keep his focus in game 13 of the Candidates.

Anand was on the other hand not in control over his reaction to the pressure of playing Carlsen. When he did not take on b2 in game three, because it would probably be a draw anyway, he did not put pressure on his opponent, and he was not able to resist the pressure when it was applied to him.

Carlsen has said that his most difficult future opponents would be Kramnik and Caruana. Personally I believe in Kramnik in the Candidates in the spring. I also believe that we will have an entirely different match next time with a challenger that fears nothing and no one. The winner of the Candidates will have these abilities; because otherwise he will not be able to win it. For this reason I believe in Kramnik more than anyone, but also think that Topalov could come through, though he is not as strong as he was at one point.

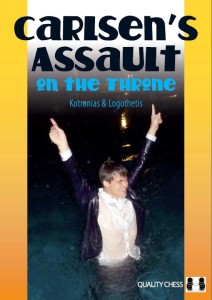

Finally, it is a pleasure for me to announce that we have been working on a little side-project called Carlsen’s Assault on the Throne. It goes to the printer in a few days and will, with luck permitting, be presented at the London Chess Classic. It will be available everywhere else on the 18th December together with From GM to Top Ten and Grandmaster Repertoire 15 – The French Defence Volume Two.

Recent Comments